Periodontitis

Periodontitis

Periodontitis is characterised by the loss of gingival and periodontal tissues. Patients present with a variety of signs including interproximal recession, increased periodontal probing depths, bleeding on probing, mobility of teeth, drifting or loss of teeth and signs of infection with pus on probing. Periodontitis is a result of plaque-induced inflammation that results in loss of periodontal attachment (see figure: Periodontitis).17

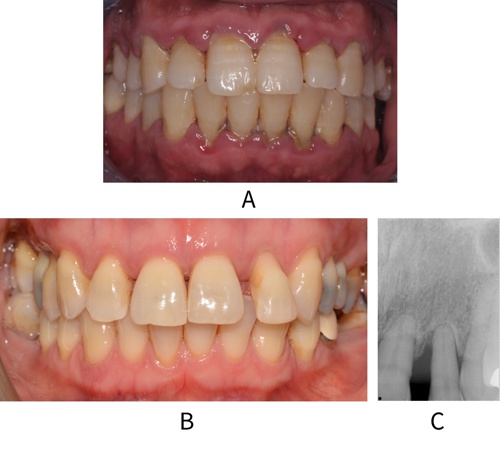

A: Image of a patient with generalised periodontitis and significant gingivitis.

B: Patient with drifted tooth 22 secondary to periodontitis (image C) but no gingivitis

The 2018 Classification of Periodontal Diseases defines periodontitis as interdental clinical attachment loss detected at ≥2 nonadjacent teeth.*17 Typically, patients with periodontitis will present with pockets ≥4 mm and/or evidence of interdental recession.

A diagnosis of periodontitis should include identification of the disease type§ and extent, the stage and grade of the disease, the current periodontal status and a risk factor profile. Patients with evidence of historical periodontitis (signs of interdental recession or radiographic bone loss) should also have the stage and grade of their disease assessed and a diagnostic statement recorded.

An example of a diagnostic statement for a patient with periodontitis is:

Generalised periodontitis; Stage II, Grade B; currently unstable; risk factor: current smoker <10 cigarettes/day

*As CAL can be associated with clinical conditions other than periodontitis, the requirement for CAL to be detected at ≥2 non-adjacent teeth is intended to increase diagnostic accuracy and avoid a diagnosis of periodontitis being made on the basis of atypical sites.

§ Three different forms of periodontitis have been identified; periodontitis, necrotizing periodontitis and periodontitis as a direct manifestation of systemic diseases. The latter two forms are discussed in more detail in Other periodontal conditions.

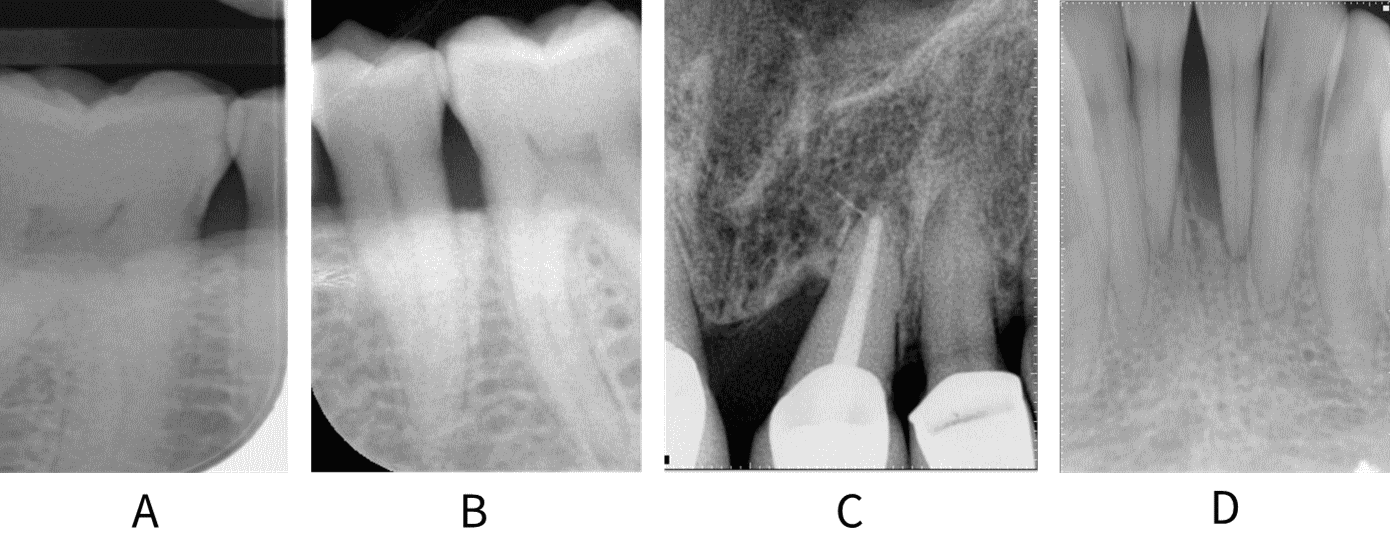

The Stage of periodontitis reflects the historical severity of disease. The Stage of disease is diagnosed using radiographs, ideally those showing the full extent of the root length, and reflects the severity of bone loss at the worst affected site in the mouth (see figure: Stages of periodontitis).

To Stage disease, the worst affected tooth in the mouth is identified radiographically.¥ The amount of bone loss at that worst affected tooth is then calculated as a percentage of the tooth’s total root length. This percentage bone loss is used to determine the Stage (i.e. I – IV) of periodontal disease for that patient overall (see table: Staging periodontal disease). Expressing bone loss as a percentage makes this aspect of diagnosis more objective and allows for easier communication between clinicians and patients.

Where radiographs are not available, or where only bitewing radiographs that do not show the full extent of the root are available, estimates derived from measurements of clinical attachment loss (CAL) relative to the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) can be used if there is no other clinical indication to take another radiograph.

Staging periodontal disease37

| Stage | Description | Amount of bone loss* |

| I | Early/mild | <15% (Alternatively, >2 mm but <4 mm bone loss on bitewing or, if radiographs not available, <2 mm CAL from CEJ) |

| II | Moderate | Coronal third of root |

| III | Severe | Mid third of root |

| IV | Very severe | Apical third of root |

*bone loss must be due to periodontitis, i.e. not due to root fracture, third molar removal etc.

Where a patient is known to have lost teeth due to advanced periodontal bone loss, then a stage IV classification may be immediately assigned.

Radiographs showing A: <15% bone loss between 46 and 45; B: bone loss within the coronal third of the root at 35, 36; C: middle third bone loss on mesial aspect of 21; D: apical third bone loss interdentally at 31, 41.

Diagnosis of early-stage periodontitis may be difficult, and overdiagnosis of disease can be an issue, especially if only bitewing radiographs are available. In these cases, a diagnosis of Stage I periodontitis is assigned if there is >2 mm bone loss but not more than 4 mm. If radiographs are not available, % bone loss can be estimated using CAL from the CEJ; a diagnosis of Stage I periodontitis is assigned if CAL is <2 mm from CEJ.

¥ The bone loss at this site should be due to periodontitis and not for other reasons, such as a root fracture or a previous surgical intervention (for example, wisdom tooth removal).37

The Grade of periodontitis is a measure of the rate at which bone loss has occurred and reflects the patient’s susceptibility to disease.

The Grade is determined by dividing the percentage bone loss observed at the worst affected site by the age of the patient in years (see table: Grading periodontal disease).

This can be quickly estimated using the following rule of thumb: assign grade A if the maximum % bone loss is less than half the patient's age in years, grade C if the % bone loss is more than the patient's age and grade B for all other patients. For example, a patient aged 45 with 50% bone loss at the worst site in their mouth would be grade C.

Grading periodontal disease37

| Grade | Ratio of bone loss to age in years* | Explanation |

| A | <0.5 | Slow progression (% bone loss < half of patient’s age in years) |

| B | 0.5-1.0 | Moderate progression |

| C | >1.0 | Rapid progression (% bone loss > patient’s age in years) |

*N.B. The UK implementation37 simplified the Grading of periodontitis. In the BSP interpretation, the Grade of periodontitis is based solely on the percentage of bone loss at the worst affected site in the mouth.

The extent/distribution of disease is a measure of how many teeth in the dentition have been affected by periodontitis (see Figure: Extent/distribution of disease). It is determined by assessing what proportion of teeth in the dentition have lost supporting bone (see table: Extent/distribution of bone loss).

Extent/distribution of bone loss37

| Description of extent | Distribution of affected teeth |

| Localised periodontitis | <30% |

| Generalised periodontitis | >30% |

| Periodontitis molar/incisor pattern | Molar/incisor |

Extent/distribution of disease

A: Radiograph showing localised bone loss. B: Radiograph showing molar incisor pattern bone loss. C: Radiograph showing generalised periodontitis with >30% of teeth affected by bone loss.

The stability of disease is a reflection of the current level of disease activity.

Assessing the stability of disease relies on measuring both the extent of bleeding on probing (BoP) and the level of probing pocket depth across the dentition (see table: Stability).

Determining current disease status is important to monitor the response to previous periodontal treatment and for onward treatment planning. Stability is a dynamic state; a patient with a diagnosis of periodontitis who is assessed as stable remains a periodontitis patient for life, as sub-optimal maintenance of the disease and uncontrolled risk factors can cause the disease to recur.

Stability37

| Current disease status | Definition |

| Stable | BoP <10%; PPD ≤4 mm; no BoP at 4 mm sites |

| Remission | BoP >10%; PPD ≤4 mm; no BoP at 4 mm sites |

| Unstable | PPD ≥5 mm (or ≥4 mm with bleeding at those sites) |

N.B. Probing depths of 5 or 6 mm in the absence of bleeding on probing (BoP) may not represent active disease, particularly in patients who have recently received periodontal treatment. This should be taken into account when deciding whether to provide additional treatment such as further instrumentation or surgery at those sites.

Identifying risk factors for disease allows assessment of features which impact a patient’s current status and their risk of disease progression, and which may also impact their response to treatment and future prognosis.

Risk factors should be identified as part of the diagnostic statement. The BSP suggest that the risk factor profile should be documented alongside the diagnosis and provide examples of relevant risk factors (e.g. smoking and diabetes).

For systemic risk factors, the highest certainty evidence relates to smoking and diabetes. However, this list is not exhaustive and emerging evidence suggests other relevant systemic risk factors, for example stress and obesity, may play a role. Local risk factors, for example crowded teeth or marginal overhangs, may also be important and their recognition as part of the diagnosis will inform treatment planning (see Risk factors for periodontal diseases).

Refer to Managing risk factors for more information on the control of risk factors.